Paul Mardikian has been front and center for every phase of the Hunley’s restoration.

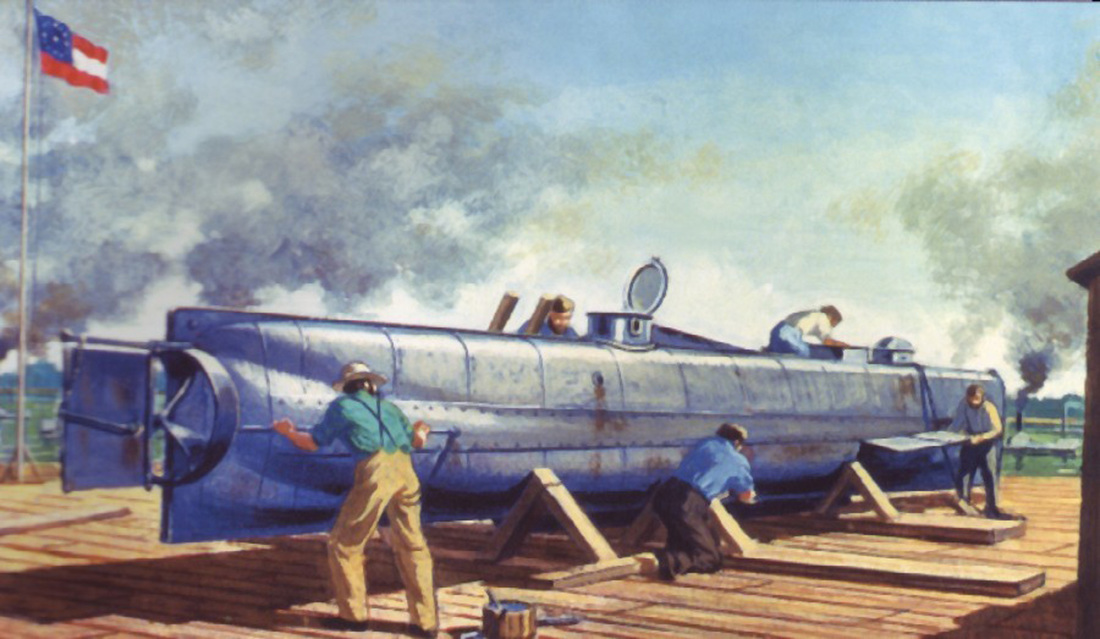

Without this critical maneuver, team archaeologists say that the latest phase-removing the sub’s heavy coat of concretion-would have been all but impossible. To everyone’s relief, the project went smoothly and the sub was finally freed from a thicket of heavy slings that had held it in place for eleven years. Even after the recovery of the crew’s remains and dozens of artifacts, the team knew that rotating the vessel still posed the threat of irreversible structural damage. Archaeologists feared that righting it might destroy priceless archaeological clues that remained inside. Discovered resting on the seafloor at a 45-degree angle, the sub was recovered exactly as it was found. Dixon.Īfter years of study and intense debate, in 2011 the sub successfully underwent a risky procedure in which it was rotated to its original vertical position. That excruciatingly painstaking work culminated with the recovery and analysis of the remains of the sub’s eight-man crew, including the Hunley’s twenty-seven year-old skipper, Lieutenant George E. Four years later came the excavation of the sub’s interior, filled to capacity with thick, gooey sediment. Obviously the first, which drew world attention, was the recovery of the submarine itself from its muddy grave, moving it ashore and setting it up in a highly specialized holding tank. So far, the exhaustive restoration work has been punctuated by four pivotal events. Stages of recoveryĮven before the de-concretion process began in 2014, the team of conservators hoped the work would reveal tantalizing clues about the Hunley’s final moments, solving one of the Civil War’s most puzzling mysteries. As detailed in Learning from the Hunley, the story of the Hunley’s 1995 discovery and subsequent resurrection has focused international attention on Clemson’s efforts. The twelve-member team Cretté now leads (the center’s first director, Michael Drews, retired in 2012) has evolved over the years but remains focused on finishing one of the most challenging restoration projects in American maritime history. The caustic bath draws salt from the Hunley’s iron pores, a slow but effective remedy from the effects ofsoaking in seawater for well over a century. The group has arrived on one of the three days each week that the Hunley’s 72,000-gallon pool of dilute sodium hydroxide is drained to allow conservators to do their work. “By this time next year, we hope to be done with the next phase, which is (cleaning) the interior,” Cretté says as she helps visitors don rubber boots, safety glasses, and latex gloves for their descent into the Hunley’s damp home. Since its founding in 2004, the institute has parlayed its oversight of the Hunley project into a busy hub of innovative research on the banks of the Cooper River in North Charleston (see Defining the wind). Home to the Hunley, the center is a cornerstone of the Clemson University Restoration Institute. It’s the first time anyone has seen this in more than a hundred and fifty years,” says Stéphanie Cretté, director of Charleston’s Warren Lasch Conservation Center. “We are now seeing the actual surface of the submarine. The work, which took a solid year to complete, was long awaited not only by the Hunley’s caretakers but by maritime archaeologists the world over. This summer, the team celebrated the end of the tedious job of removing all of the material, called concretion, from the Hunley’s iron hide. They chip away the last patches of sea-made crust-residue collected from 136 years of resting on the bottom of Charleston Harbor-from the sub’s hull.

The raucous sound of mad hornets comes from a team of conservators wielding small, but noisy, pneumatic chisels. Shorn of its thick, hardened coat of sand, sediment, and shell, the naked submarine is offering researchers their best clues yet about how the manpowered sub worked and why it famously disappeared after sinking a Union warship blockading Charleston in 1864. Or so it would seem from the noise boiling out of the tank where the world’s most famous submarine has rested now for fifteen years.įinally freed from near-constant immersion in a pool of fresh water-its protective bath since being raised from Charleston Harbor in August 2000-for the first time in 151 years the old sub is showing itself in all of its raw, ironclad beauty. An angry swarm of hornets has invaded the home of the H.L.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)